In celebration of World Kindness Day, this month’s blog posts focus on kindness and prosociality in video games. It is a timely topic, as the majority of popular video games nowadays allow (or even require) multiple players to join in at the same time. More than ever before, gamers are being dropped in virtual worlds together with their friends, family, but also total strangers. What kind of effect does this social dimension have on our behavior?

People’s experiences with multiplayer games aren’t always the positive, affable interactions that one would hope for. The online community is rife with example of players engaging in offensive remarks against one another, or deliberately hindering and irritating others to ruin their in-game experience (a practice called griefing). These kinds of actions are examples of toxic behavior. With the rise in popularity of social games, toxicity is becoming increasingly problematic. Research on the consequences of toxicity in games is scarce, but there is always a danger of persisting emotional effects on players even after a game is turned off. Thankfully, game developers are aware of toxic behavior and try to address it through their design.

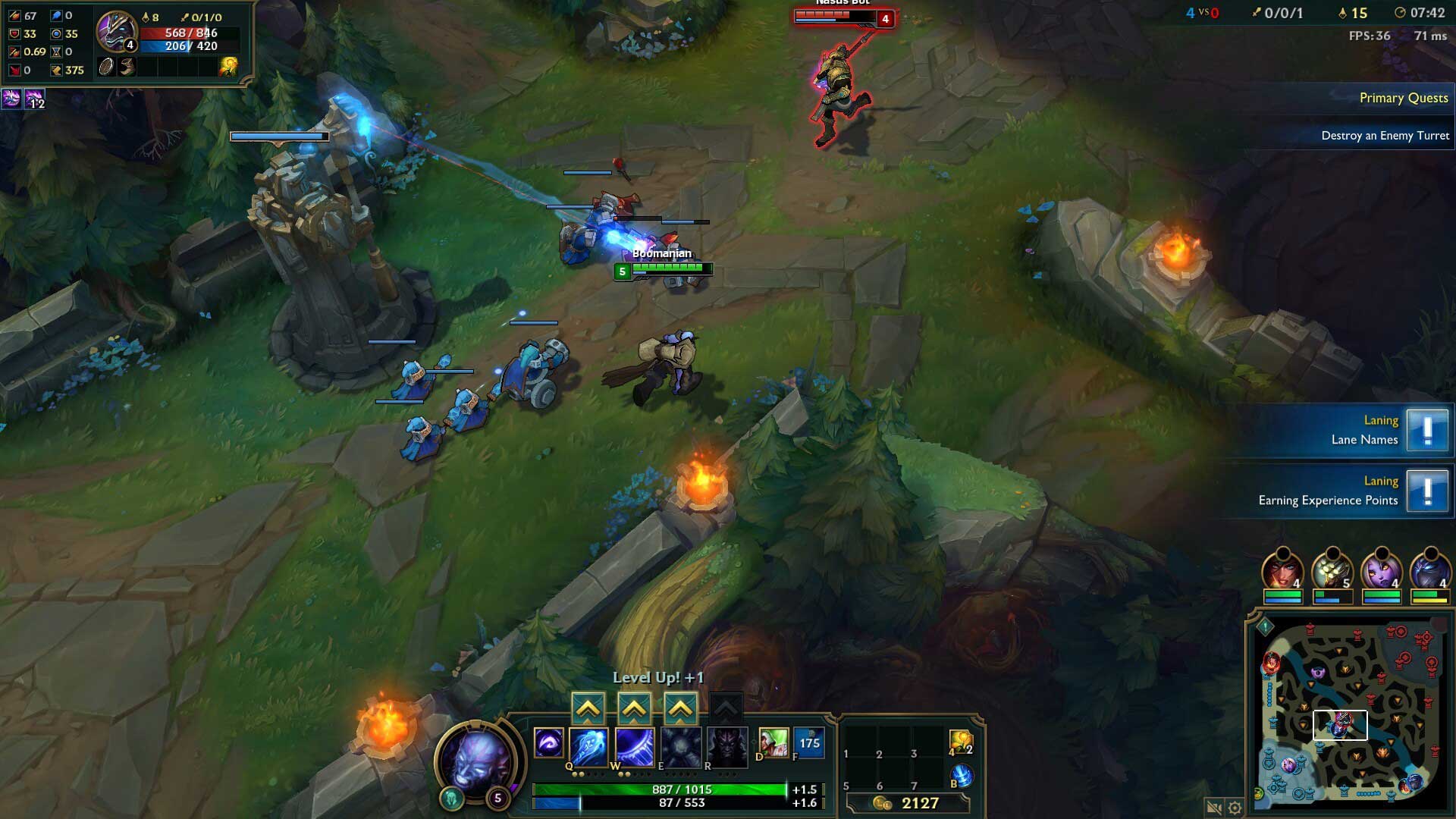

One company that has taken a clear stance against toxic behavior is Riot Games, known for their famous MOBA game League of Legends. In this game, two teams of five players each cooperate to kill monsters, capture territory and ultimately destroy the other team’s base. Unfortunately, perhaps due to the highly competitive setting, toxic behavior is frequently displayed towards (poorly performing) teammates. Riot Games tackled this problem openly, using good old-fashioned research to test different techniques that they predicted would ameliorate toxicity. Among their findings was that presenting some stimuli can be used to nudge people’s behavior in a certain direction afterwards—a concept known in psychology as priming. For instance, displaying a tip that “teammates perform worse if you harass them after a mistake” reduced negative attitudes and offensive language afterwards. Interestingly, this effect was strongest when the message was displayed in red, perhaps due to that color being associated with error avoidance. Findings such as these, coming straight from the industry, are incredibly valuable for us scientists. The research by Riot Games is summarized in an awesome article published by the scientific journal Nature (1).

Of course, the absence of toxic behavior does not equal positive interactions. Instead of trying to prevent or combat toxicity, some games seem to actively promote kindness and prosociality. For me, a prime example of a game that takes this approach is Journey. In this adventure/platformer game, you control a character that has to traverse towards a mountain in the far distance. While the game starts out as a solitary experience, players may come across one other player that temporarily connects to their game. As humans are social creatures by design, the majority of people seem to be drawn towards this other person. The trouble is, however, that players have very little ways to communicate with one another in Journey. Characters aren’t able to talk or message, although they can create a (rather ambiguous) chime sound. What happens then is very interesting: players often opt to travel together, and help each other to progress or find secrets. In my own experiences, the game caused prosocial behavior to emerge naturally and without explicit incentives.

I remember attending a presentation a couple of years ago by the producer of Journey, Robin Hunicke. She explained how they made the design choice to remove ‘power tools’ from their game, meaning the different ways that players could dominate one another. In Journey, players cannot hinder each other in any way, but they are also not required to cooperate to progress through the game. Perhaps this is why the in-game behavior is drawn towards friendly and kind-hearted interactions. While it was several years ago, Robin’s presentation always stuck with me as an example that clever game design can have a great deal of influence on player behavior.

I’m not sure if the multi-player system in Journey was actively designed to promote prosocial behavior. In an interview from 2011, Robin Hunicke stated that removing communication options to facilitate connections was an experiment (2). However, our own experiences with the game has led to observations that inspire future research questions and game design. Findings and ideas as described above could help us understand how we can make sure that games steer away from problematic actions, as well as nudge us towards healthy behavior. While working in academia, it is easy to forget how much knowledge is already garnered by the industry, as well as experienced by gamers themselves. The examples above illustrate that design choices can go a long way in shaping in-game behavior, and hopefully also out-of-game behavior.

If you have any experiences of spontaneous emerging kindness and prosociality in video games, please let us know in the comments below!

References

(1) Maher, B. (2016). Can a video game company tame toxic behaviour? Nature, 531, 568-571. doi:10.1038/531568a

(2) Stuart, K. (2006, December 6). Robin Hunicke on Journey, AI and games that know they're games. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/technology/gamesblog/2011/dec/06/journey-preview-robin-hunicke-interview