The recent reveal of a “super easy mode” in the much anticipated game Death Stranding re-ignited a debate within the gaming community about whether games should be challenging, and whether measures to make games more accessible are actually detrimental to the gameplay experience. Kyle Orland summed it up very well in his article for Ars Technica, in which he advocates for all games to include ways to overcome gatekeeping (locking portions of the game until certain levels are beaten). However, Orland found a prolific detractor in Mark Kern, a former producer at Blizzard Entertainment and one of the key people behind World of Warcraft. Kern and his supporters argue that a challenging game builds resilience, and that having to try something over and over again until you succeed is exactly what makes notoriously difficult games like Dark Souls such a rewarding experience. Taking that challenge away would negate a game’s emotional impact.

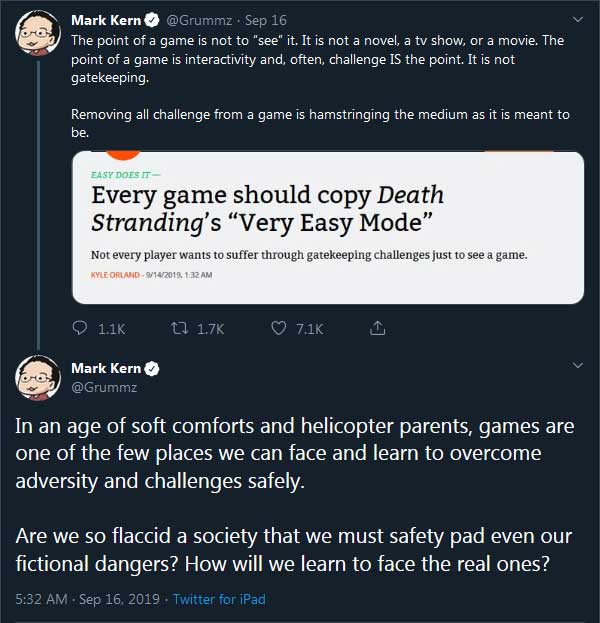

Kern responding to the Ars Technica article on Twitter. He later clarified his point was to say not *all* games need an easy mode.

Admittedly, my first reaction was to agree with Kern. Not that games should inherently be challenging, as was immediately disproven by Twitter user XCK3D, but that it is OK for some games to be hard by design. Then I played the newly released Sayonara Wild Hearts this weekend, and it changed my mind.

Sayonara Wild Hearts (SWH) calls itself a “pop album video game”, but at its core it is a combination of a runner game and a rhythm game. Those are two video game genres I have never been very skilled in, and that often involve heavy gatekeeping. I was therefore hesitant to even try the game, but the unique premise and art style won me over (also Annapurna Interactive has yet to publish a bad game).

Seconds into playing the game, I was hooked. An enchanting, synthesized version of Debussy’s “Clair de Lune” echoed through my living room as I steered the game’s skateboarding heroine across a rainbow-colored road in space. At the end of this first level, the game rewarded me a bronze rank for collecting hearts along the way (silver and gold being better). Enough to proceed, apparently, and assuming I had mastered the basic controls, the game picked up the pace. It wasn’t long until I started to struggle and ended a level with a score below the bronze threshold. “NO RANK”, the narrator informs me, while I’m already mentally preparing to replay the stage. To my surprise, the game progressed to the next level regardless. It dawned on me that developer Simogo was serious about calling this a “pop album video game”. Sayonara Wild Hearts does not care about how good you are, it just wants you to enjoy the songs as if listening to an album, non-stop, while simultaneously letting you take part in their MTV music video.

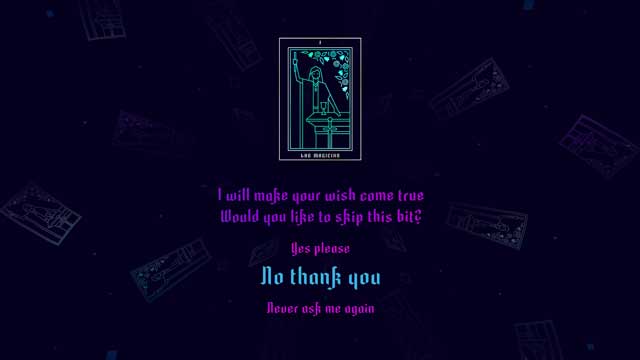

I discovered other design decisions Simogo made to keep the player in a continuous state of flow, regardless of skill level. The time window for responding to quick time events is very loose (but you get extra points for getting it right). When crashing into a roadblock, instead of a game-over, the game quickly rewinds to the start of the section and sends you straight back in. Fail in the same section 5 times and a screen pops up to let you skip that part (or try again). Complete the game and you unlock “Arcade Mode”, which allows you to replay the entire game without level-breaks or score-updates all together.

Sayonara Wild Heart offers players to skip a difficult section, or let them persevere.

I finished Sayonara Wild Hearts and absolutely loved every bit of it. The game understood that I had alternative motives for playing, and provided me with tools to set my desired level of challenge. I skipped a section once, and persevered some other times. I got 2 silver ranks that made me feel proud. I want to replay the game to try and get one or more gold ranks. Not because the game demands it, but because I want to. It’s been an exhilarating and liberating experience; one that I–like Kyle Orland–wish all games would be able to provide.

What motivates you to play a game? Have you ever given up on a game because it was too difficult?