Games can show us a reflection of who we are

Games provide a very interesting avenue to explore morality. After all, you are not hurting any real people when you allow yourself to misbehave within games. I’m sure we’ve all done things in game worlds that we are not proud of, just to see what happens. In this way, games can provide us with an idea of the consequences of certain actions, and provide an opportunity to test how those actions affect us emotionally. Although making selfish choices can be fun for a while, perhaps you may also discover that going out of your way to help other people makes you feel better about yourself?

Moreover, games can allow us to test the assumptions we have about ourselves. For example, recently I got in a fierce argument with a good friend of mine when we compared outcomes of a particular Telltale game and discovered we made completely opposite choices. We both felt our choices were without a doubt the obvious morally correct ones. I was astonished that someone who had received all the same facts as me could come to such a different conclusion. It opened up the possibility that my assumptions about myself are not set in stone: Am I actually doing good? Is my worldview correct? Why do I decide to do the things I do?

Why I try to do good

I’d like to think of myself as a selfless, empathetic person. I find it hard to do ‘bad’ in video games when I’m given a choice. I just feel too guilty, and I feel sorry for the NPCs in the game.

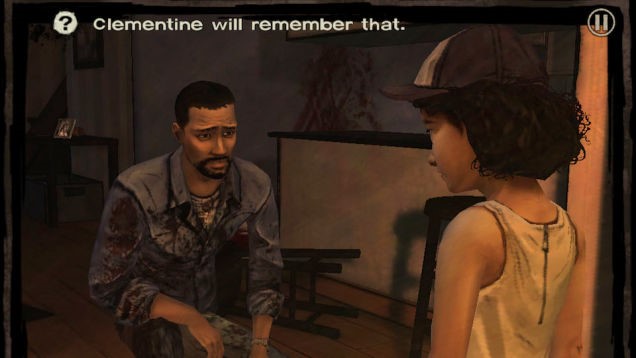

Back when my brother and me used to play Halo on the original Xbox, I actually used to cry at him whenever he used his vehicle to hit the little marines that were trying to help us. I am the kind of person that has a 99% paragon score in Mass Effect games. The “Clementine will remember that” text that pops up whenever you make morally questionable choices in The Walking Dead still haunts my dreams.

Don’t you judge me, Clementine. I am trying to do what’s best for you!

However, the context of the game is of vital importance to me. I have no qualms about conquering the realm of men with my devilish monsters in Dungeon Keeper. And when playing Grand Theft Auto, I will gleefully rob convenience stores and have little regard for pedestrians crossing the street while driving like a maniac through the city. What makes those games so different from the ones where I agonize over my every choice?

Maybe it is how developed the characters are? Or maybe it is the consequences attached to my actions? For example, Grand Theft Auto is built around you as a character being a criminal. While bad behaviour results in the police chasing you down, the game is designed so that police are easily shaken off, making it actually fun to see how many ‘wanted stars’ you can get and how long you manage to stay alive before getting caught.

Let’s play the game of ‘how many police helicopters can I get to chase me before they stop my rampage?”

Moreover, getting caught has no consequences on the world, nor does robbing stores or running over the occasional pedestrian. You pay a fine, or you ‘die’, and you get released from prison or the hospital; the world resets, people forget who you are and nothing has changed. You are free to continue your mistakes, and more importantly nobody seems to hate you for it.

On the other hand, games that spent time building up character choices, that track your morality or show the actual consequences of your actions feel much more intimidating. One mistake or one selfish choice, and the people will forever remember me as a bad person. These games somehow make me belief in the illusion that the little digital folks walking around on my screen are actual people, and therefore have a right to life and happiness. They impress upon me a need to see them content: I feel personally responsible for their happiness, and most of all I want them to like me.

Unfortunately, it is this exact need that led me to a series of decisions that culminated into probably the worst thing I have ever done in a video game.

Maybe not so selfless after all

(The following text contains ending spoilers for Fable III)

The worst thing I have done in a game took place in Fable III. In this game you can make decisions based on doing good or evil. The path you walk determines the way you look and the way people view you. Naturally, this means I decide to do as much good as possible, because I am nothing if not predictable.

In the game, you work your way up from a lowly outcast prince or princess, to a respected adventurer and eventually the new ruler of the land Albion. Albion is a fantasy land that has recently entered the age of industry. When you start out, Albion is being ruled by a tyrant who works his people to death. His name is Logan, and he is actually the older brother of the player’s character. Under Logan’s rule there are now things like child labour, executions, many polluting factories, and a whole lot of misery. He is the epitome of evil.

Logan even seems to have the whole evil aesthetic going on.

Throughout the game I helped free the people of Albion and forged alliances with allies to help overthrow the tyrannical rule of my evil brother. I promised I would rebuild their lands and their homes. I promised I would lower taxes, provide care for the poor, and provide refuge to a nomadic people. I promised a lot.

Near the end of the game, I uncovered the truth behind Logan’s terrible actions: There is a monster called the Crawler, commanding an army of shadow creatures, which aims to exterminate all life in Albion. It had already overrun and destroyed the land of Aurora, whose people I actually promised refuge in Albion if they helped me overthrow my brother. In the end, it turned out the reason Logan was having the people of Albion work to death was because he was trying to create enough firepower and raise enough money to stave off the attack of the forces of evil.

Of course, I eventually usurp Logan and become the new ruler of Albion. I decide to let my brother live, but now all my allies visit me one by one asking me fulfill my promises:

Do I rebuild part of the city, or leave it in ruins and its people homeless? Do I increase spending on guards to help protect people from crime, or do I fire what guards are left so I can spend that money elsewhere? Do I open up an orphanage, or turn it into a brothel? Do I protect the surrounding lands by building a sewage plant, or do I dump the sewage in a nature reserve?

Press X to be evil. Press A to be good.

Most of the choices are very black and white, but the promises I made to my allies weigh heavy on me. I succumb to the will of the people and try to give them everything they want. I would like to see them happy.

Unfortunately I don’t have a knack for completionism, so my personal funds gained through adventuring are not nearly enough to replenish the quickly dwindling gold reserves of my royal treasury.

One day, after I decide to lower taxes, my treasurer comments:

“The people will be delighted, your majesty. But will they thank you when they are dead?”

I try to ignore his warnings. There are still plenty of decisions left to make after all! An endless parade of keeping promises or breaking them. Surely I have enough time left to turn this around? However, I can’t force the people of Aurora into slave labour in the mines, right? No, I’d better provide them with safety and homes first.

In the end my allies thank me and my people are happy. I feel content and accomplished.

A year passes. And the Crawler comes for Albion. There is long, arduous fight, but in the end I manage to defeat evil… and win!

Or do I?

“You have defeated a formidable enemy, but at a cost beyond measure. The tiny handful of survivors and their descendants will forever remember you as the ruler who let the kingdom perish.” - The game informs me.

When the game returns me to my kingdom, I walk through the empty city streets. I find my people lying motionless on the ground. They are just pixels; digital representations of generic villagers that aren’t even real. But the world feels empty, and all my good choices seem meaningless now. This game has confronted me with the consequences of my actions, consequences I had not even considered before and it made me realize something: If I were to save these people, was I truly meant to turn into the very thing that I set out to destroy? I would have needed to betray my word; my allies would have been repulsed.

Maybe the lesson was that by trying to go out and please everyone, I lost sight of the end goal. I was now a bankrupt queen with lands without inhabitants. I indeed let my kingdom perish.

But at least the people told me they liked me before they were wiped out, right? In that, perhaps, all my choices were a selfish act all along.

Luckily, I only needed the death of a virtual kingdom for me to realize that.